Commonplacing as a Learning Tool for a Purpose-Driven Life

My system for commonplace notebooks and why they're an invaluable part of my ongoing learning journey

In our digital age, it’s easy to keep track of ideas, quotes, and references with a few clicks or taps. But before bookmarks and cloud storage, people had another way of collecting their thoughts and the wisdom they encountered along the way: the commonplace book.

These personal, curated collections of knowledge are surprisingly old, and their evolution is fascinating, reflecting centuries of intellectual life before “personal knowledge management” was even a concept. Let’s explore the origins and evolution of commonplace books and their enduring appeal through the ages.

A commonplace book is essentially a collection of ideas, quotes, reflections, and notes, kept together in one place by the person who wrote it. While that might sound like a random notebook, there’s usually some form of organisation involved. The entries might include anything from memorable quotes to philosophical reflections, recipes, poems, or tips. The goal was to create a personal knowledge hub—not just gathering information, but actively digesting it to make sense of the world.

The History of Commonplace Books: The Original Knowledge Repositories

But the tradition of collecting ideas, knowledge, and reflections in one place goes back centuries, and it finds one of its richest expressions in the commonplace book. The idea of loci communes (Latin for “common places”) became popular among Greek and Roman scholars, who would note down anything worth remembering. For example, Roman orators like Cicero saw value in keeping handy collections of wise sayings and passages for use in speeches and debates.

By the Middle Ages, monks and scholars had their own versions of commonplace books, called florilegia (literally “flower collections”). These early versions weren’t as personal as later commonplace books, but they were still ways of gathering wisdom from religious texts, classical works, and poetry.

The Renaissance: Commonplace Books Come Into Their Own

During the Renaissance, there was a revival of this practice as scholars, writers, and thinkers wanted to organise and keep the ideas they encountered. Thinkers like Erasmus encouraged students to jot down ideas and quotations, believing it was a great way to engage with knowledge and spark creativity. In fact, many Renaissance commonplace books became highly organised, divided into themes and topics that matched the interests of their creators.

These books were not just for storing knowledge but also for working with it. Renaissance scholars could compare thoughts on everything from virtue and politics to the human condition. These books became their personal libraries of wisdom—sort of like a one-stop shop for inspiration.

The Golden Age of Commonplace Books: 17th and 18th Centuries

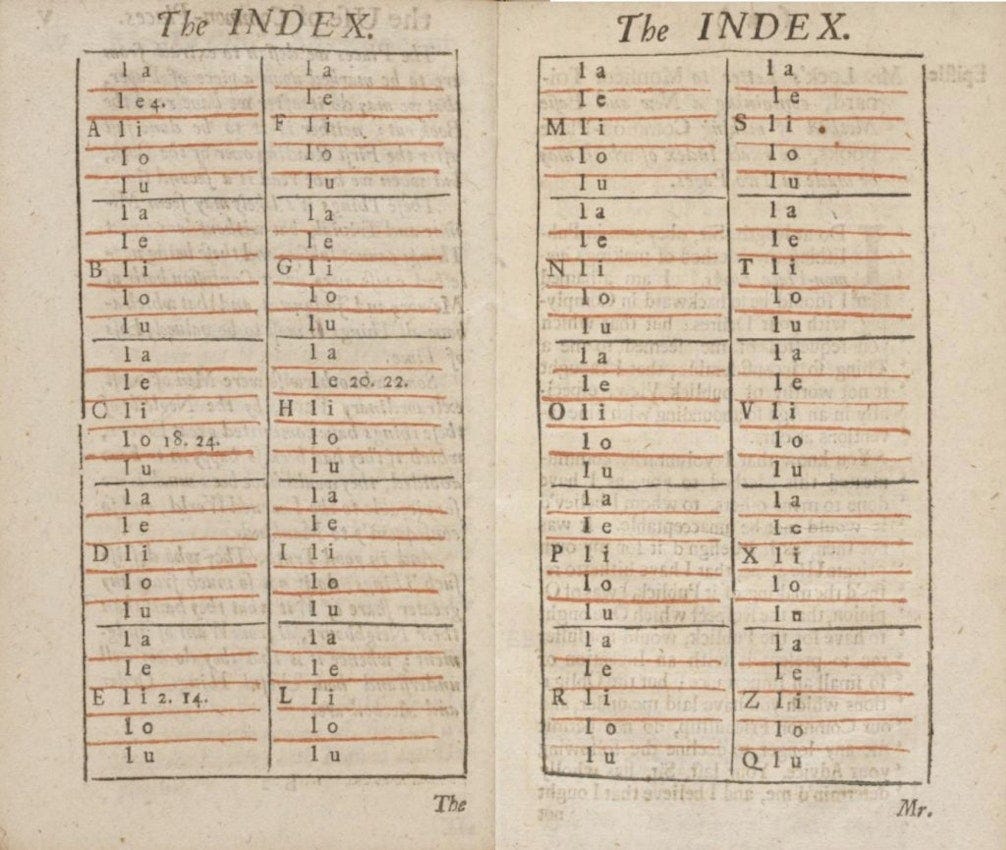

Commonplace books really hit their stride in the 17th and 18th centuries. Writers, thinkers, and students began to keep detailed commonplace books, often organizing them alphabetically or by topics. It wasn’t just scholars who kept them, either—many members of the educated public had commonplace books. John Locke, the English philosopher, even created a method for keeping a commonplace book that encouraged a systematic approach, with indexing to make it easier to reference later.

In the 18th century, authors like Samuel Johnson and Thomas Jefferson were avid commonplacers, keeping extensive collections of quotes, ideas, and personal reflections. At a time when information wasn’t so easy to access, these books were an incredibly useful way to store and process ideas for later use in writing and conversation.

Romantic and Victorian Eras: More Than Just Knowledge

By the 19th century, commonplace books took on a slightly different flavour. They were still used for scholarship, but they became more personal, with writers and thinkers using them to document their own reflections and feelings. During the Romantic period, writers began to use commonplace books almost as journals, mixing in personal insights with quotes from literature and philosophy.

In the Victorian era, these books often became beautiful objects in their own right, carefully handwritten and sometimes even decorated. They were personal treasures, often passed down through families, giving future generations a glimpse into the intellectual and emotional lives of their ancestors.

The Decline and the Digital Resurgence

As we entered the 20th century, commonplace books became less common. With access to printed books and reference materials becoming easier, the need to write things down in a personal book seemed less urgent. But even though they faded from popular use, the concept of a commonplace book didn’t disappear entirely. With the rise of digital tools, people today are creating modern versions with apps like Evernote, Notion, and Roam Research, using these digital “commonplaces” to organise and connect ideas.

Why Commonplace Books Still Matter

The tradition of the commonplace book is a powerful reminder of the value of slow, reflective learning. Instead of just skimming information, keeping a commonplace book encourages us to take in ideas and connect with them deeply. By carefully recording and organising knowledge, we create a resource that’s both practical and meaningful. In a world overflowing with information, there’s something timeless about curating our own little libraries of wisdom.

My Commonplace Framework: at the Intersection of Notebooks, Journals, and Sketchbooks

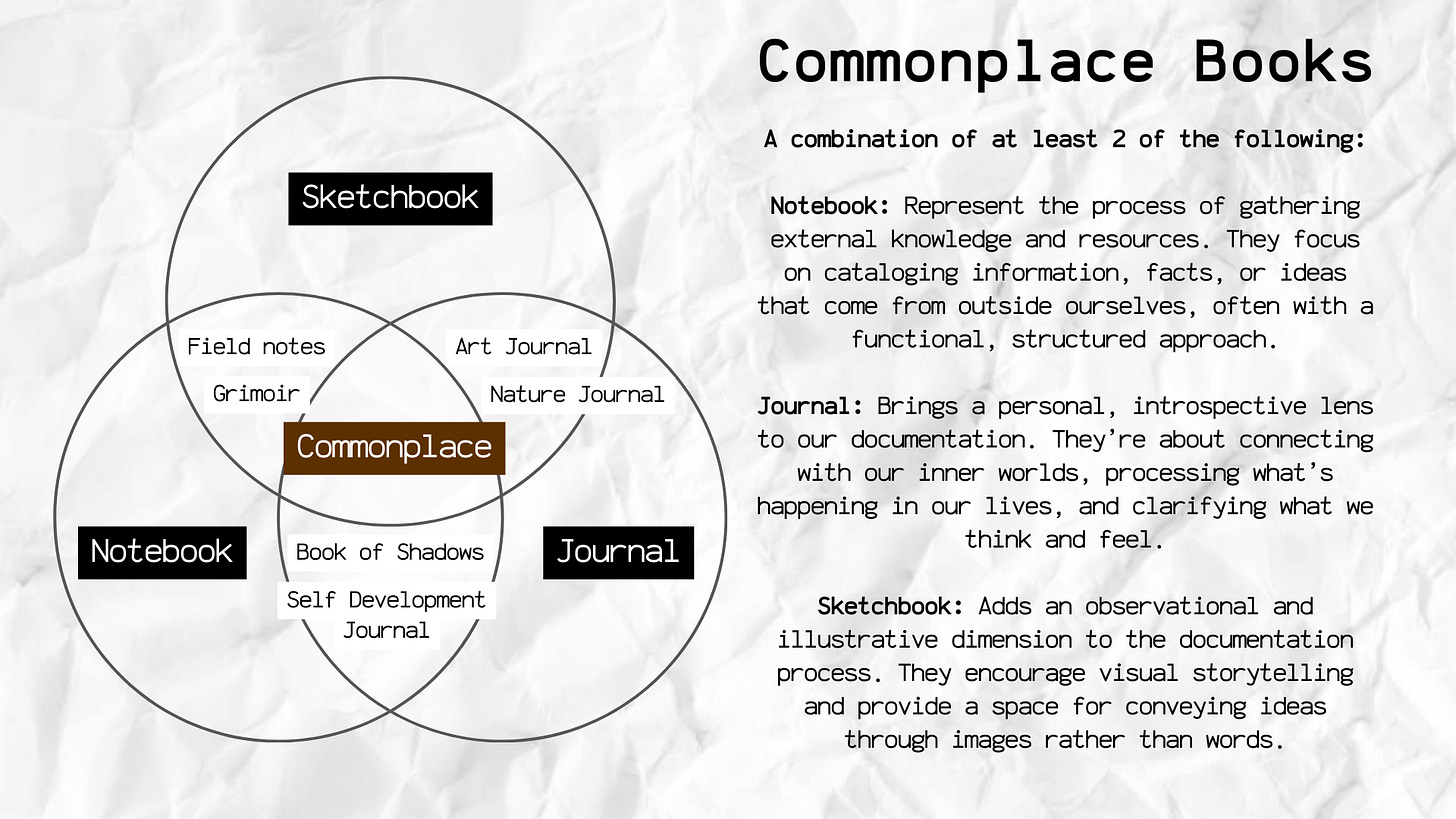

When we think about capturing ideas, reflections, and observations, we often reach for notebooks, journals, or sketchbooks—but each of these tools has a distinct purpose. To make sense of how these forms of documentation overlap and differ, I created a framework that places a commonplace book at the heart of this triple Venn diagram. Commonplace books often encompass qualities of all three forms: they capture both the external and the personal, blending written and visual documentation to create a unique record of knowledge. In my framework, the commonplace book sits at the intersection of notebooks, journals, and sketchbooks—each adding its own dimension to the art of recording and organising ideas.

The Three Pillars of Documentation

Let’s break down the unique roles that notebooks, journals, and sketchbooks play, and why they are essential components in this framework:

Journals: Reflection and Sense-Making

Journals are where we record our personal reflections, thoughts, and emotional journeys. They help us process experiences, make sense of our lives, and navigate change. Whether it’s a daily journal, a self-development log, or a goal tracker, journaling offers a way to engage in deeper self-reflection.

Role in the Venn Diagram: Journals bring a personal, introspective lens to our documentation. They’re about connecting with our inner worlds, processing what’s happening in our lives, and clarifying what we think and feel.

Notebooks: Documenting Ideas and Resources

Notebooks are often practical collections of notes, ideas, and references. They’re places to jot down information from external sources—lectures, books, or conversations. This category of documentation is about capturing external information rather than internal reflections.

Role in the Venn Diagram: Notebooks represent the process of gathering external knowledge and resources. They focus on cataloging information, facts, or ideas that come from outside ourselves, often with a functional, structured approach.

Sketchbooks: Observing and Visualising Ideas

Sketchbooks prioritise visual communication. Often used by artists and visual thinkers, they capture observations and use drawing to communicate ideas or experiences. Sketchbooks let us engage with our surroundings in a more visual, observational way, allowing thoughts to take shape through images, diagrams, or drawings.

Role in the Venn Diagram: Sketchbooks add an observational and illustrative dimension to the documentation process. They encourage visual storytelling and provide a space for conveying ideas through images rather than words.

The Intersections: Where the Magic Happens

In addition to the distinct role each form plays, there’s immense creative potential at their intersections, where elements from two different types combine to form unique, hybrid practices:

Journal + Sketchbook (Art Journals, Nature Journals)

Here, personal reflection meets visual expression. Art journals and nature journals blend the introspective qualities of journals with the observational and illustrative nature of sketchbooks. For example, a nature journal might include sketches of plants and animals with accompanying notes on where and when they were observed, while an art journal can capture mood and emotion through drawings and painting alongside personal reflections.

Purpose: To document personal observations with both words and images, creating a sensory-rich record of personal and natural experiences.

Sketchbook + Notebook (Field Notes, Grimoires)

At this intersection, we see a focus on observing and cataloging external knowledge with a visual element. Field notes, for instance, are used by scientists and researchers to document findings, often with sketches that help illustrate observations. Grimoires, often associated with historical or spiritual practices, combine symbols, diagrams, and notes to catalog knowledge.

Purpose: To blend external observations with visual representations, often for functional or research-oriented purposes.

Notebook + Journal (Books of Shadows, Religious Journals, Self-Development Journals)

This intersection combines the introspective purpose of journals with the knowledge-gathering focus of notebooks. Books of shadows, for example, often include spiritual reflections along with documentation of rituals or practices, while religious journals might include both personal insights and notes on teachings or religious texts. Self-development journals are similar, combining personal growth insights with structured notes on techniques or lessons.

Purpose: To create a record that captures both external knowledge and personal reflection, often organized around a specific theme, philosophy, or goal.

The Commonplace Book: at the Centre

A commonplace book brings together aspects of all three forms, making it the perfect synthesis in this framework. Here’s why:

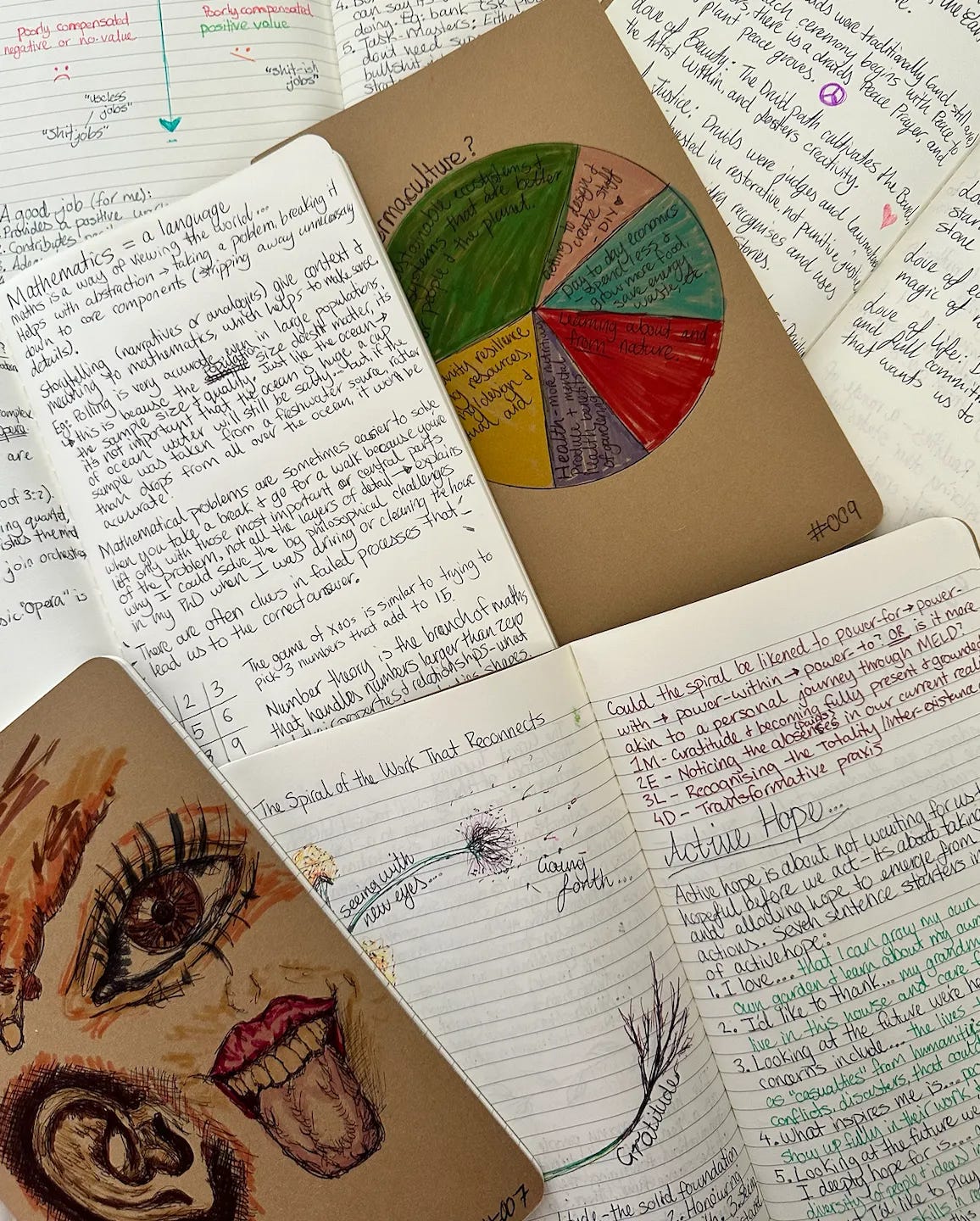

Combining Documentation and Reflection: A commonplace book gathers external ideas, quotes, and insights (like a notebook), but it’s not purely academic or practical. Often, people add reflections and thoughts, engaging with the material on a personal level.

Integrating Visual Elements: Many commonplace books also include diagrams, sketches, or doodles that help illustrate or expand on ideas. This visual element adds a creative, observational component akin to a sketchbook, turning the commonplace book into a visually enriched resource.

Flexible Structure: Unlike notebooks or journals, which often have a more rigid format, commonplace books are highly flexible, accommodating anything the creator finds meaningful or inspiring. This flexibility makes commonplace books uniquely suited to serve as a “living document” that grows and evolves with its creator’s knowledge and experiences.

The Commonplace Framework helps us understand how we can use each form of documentation purposefully. If we’re looking to capture knowledge from outside sources, a notebook might be our go-to. For personal reflections, we might use a journal. If we want to observe the world visually, a sketchbook is the perfect choice. However, a commonplace book serves as a centre point, combining all these elements, allowing for both reflection and knowledge-gathering, with the added flexibility to incorporate visual notes.

The Art of Commonplacing: Why the Process Matters as Much as the Product

Commonplacing may feel like a relic from a slower time, but it’s a practice that has surprisingly powerful relevance in today’s fast-paced, information-saturated world. At its core, commonplacing is about gathering, organising, and engaging with ideas, quotes, notes, and reflections. But commonplacing isn’t just about creating a final product—an archive of curated knowledge—it’s also deeply rooted in the process of engaging with information. This process, just as much as the final collection, is where commonplacing’s value lies.

In our digital age, where knowledge is abundant and fleeting, commonplacing can serve as a grounding practice to help us not only collect information but digest it. Here’s why the act of commonplacing, and not just the end result, is so important—and why it might be one of the most useful habits you can develop today.

Commonplacing as a Process: Why the “How” Matters

The traditional commonplace book is a deeply personal project, an ongoing curation of insights, observations, and reflections. The act of gathering these pieces of wisdom involves much more than simply saving or copying them. When you come across a powerful idea and choose to add it to your commonplace book, you're making a decision that this knowledge has value and deserves a place in your mental landscape. This act of intentional selection creates a unique form of engagement:

Active Processing: In a world where we can quickly bookmark, like, or save anything online, the practice of physically writing something down (or even digitally saving it with intention) makes you pause and think: What does this mean to me? How does it connect with what I already know or believe? Engaging with information actively rather than passively is one of the most effective ways to deepen understanding and enhance recall.

Personal Interpretation: Adding reflections or annotations to entries personalises the knowledge and helps you internalise it. Commonplacing encourages you to add your own perspective, transforming the information into something uniquely relevant to you. This personalization is powerful—it’s not just what you collected, but why you collected it.

Meaningful Repetition: The process of recording and revisiting entries reinforces the ideas over time, making them easier to remember and more likely to influence your thinking. The process helps anchor key concepts, making it more likely that they’ll become part of your long-term memory.

In short, the act of commonplacing is like an extended conversation with your learning. It makes ideas “stickier” by forcing you to engage with them, process them, and interpret them in your own way.

This is a great comprehensive article about commonplacing! Thank you for writing this!